When Phonics Doesn’t Work

Traditional tutoring for dyslexia relies on intensive instruction in phonemic awareness and the phonetic code. But such teaching is an arduous process for many students. Often progress is slow, relying heavily on repetition and “overlearning.” While basic decoding skills may improve, students may continue to lag far behind grade level, and remain hesitant and halting readers.

These students have the potential to become confident and capable readers, but they do not think or learn in the same way as typically-developing readers. When provided with strategies geared to their dominant learning style, progress can be surprisingly rapid. Davis providers have documented reading improvement of six grade levels or more, within the course of a one week program — all without attempting to teach phonetic decoding. 1

Why Dyslexic Students Struggle with Phonics

Most teachers agree that difficulty with phonetic decoding is a hallmark characteristic of dyslexia. That is the reason that most dyslexia remediation is focused so heavily on phonics. It seems to make sense to intensify instruction in the area where the student seems to struggle the most.

This teaching strategy will often work well for students whose reading delays stem from poor preparation or inadequate exposure to reading before entering school. But children with dyslexia are often labeled as treatment “resisters,” as they do not seem to progress with even the most intensive and careful instruction. Researchers report that that 30-50% of children with learning disabilities fit this category.2 3

The failure to respond to traditional intervention is so common among dyslexic students that it is now accepted as a valid alternative to formal diagnostic testing.4

Of course, these children are not willfully “resisting” anything. They struggle with phonetic strategies because their brains are wired differently. They simply are not able to categorize the sounds of language or connect sound to meaning in the same way as other students. Researchers now know that this difference is probably inborn and can be detected in early infancy.5 6

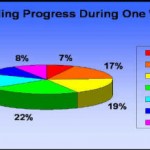

Additionally, research suggests that about 15% of children with dyslexia do not have the characteristic difficulties with phonics. Rather, if tested and diagnosed, they will be found to have a different subtype of dyslexia. They do well on tests of phonetic decoding, but have difficulty with irregular words, indicating a visual or surface type dyslexia. Phonics-based teaching won’t help that group because their reading barriers lie elsewhere. Almost two-thirds of children seem to have a mix of both types of dyslexia; for them, at best, phonetic instruction is only a partial solution.7

How Dyslexic Students Can Become Confident Readers

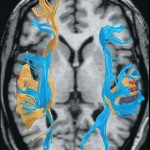

Despite early difficulties with reading, some dyslexic children become proficient readers as teenagers or young adults. Brain scientists who have studied these late-blooming readers have found a surprising but consistent pattern. The dyslexic students who become good readers develop alternative mental strategies, relying more heavily on right hemisphere and frontal regions of their brains.8 9

One long-term study of teenagers found that development of such “compensatory” brain pathways was the only distinguishing characteristic that could accurately predict which students would later become capable readers.10

In short, dyslexic students become good readers when they learn to use mental strategies other than phonetic decoding to gain reading proficiency. These strategies build upon the natural abilities of the students, teaching them to harness their strengths and use them to become accurate and efficient readers.

How the Davis Program Works

The Davis approach does not explicitly teach phonetic decoding strategies, but it provides intensive, short-term guidance and practice in just about every other area that may create barriers for dyslexic students. These strategies include:

- Specific, easily learned techniques to focus and sustain attention;

- Sensitization to internal feelings associated with perceptual errors, such as letter reversals, and to self-correct;

- A comprehensive approach to reading mastery by combined study of the appearance, sound, and meaning of words;

- Reading practice techniques to build awareness of letter sequence, whole word recognition, and sentence comprehension.

The Davis program also incorporates the techniques known to be most important for success: It is multisensory, enabling the student to learn through clay modeling combined with dictionary skill and reading practice. The formal dyslexia program is always given in a one-on-one context, with highly trained facilitator working directly with a single student.

With Davis, learning seems fun and natural. Parents typically report that their children experience significant gains in confidence and self-esteem, as well as improved reading skills. Students often reach grade level or above within the course of a one-week program, and reading becomes pleasurable as they work through the follow-up program of clay modeling and reading practice.

The Davis program is groundbreaking and different, but it is not new. The program was first implemented by its developer, Ronald Davis, in California in 1981. Fifteen years later, after working with almost two thousand students and releasing the first edition of his book, The Gift of Dyslexia, Davis began training others in his methods. Since that time, hundreds of professionals have completed a rigorous training program leading to licensing, and the Davis program is now available in more than forty-five different countries. Tens of thousands of students of all ages have benefited; in fact, some students who received the Davis program in childhood have now grown up and become Davis Facilitators themselves.

Related Articles

When Dyslexics Become Good Readers

Brain Scans Show Dyslexics Read Better with Alternative Strategies

Davis Program Average Reading Gains

References

- Marshall, A., Smith, L., & Borger-Smith, S. (2009). Davis Program Average Reading Gains.

- Torgesen, J.K. (2000) Individual Differences in Response to Early Interventions in Reading: The Lingering Problem of Treatment Resisters.Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, Vol. 15, Issue 1, pp. 55-64; Al Otaiba, S., and Fuchs, D. (2006)

- Al Otaiba, S. & Fuchs, D. (2006) Who Are the Young Children for Whom Best Practices in Reading Are Ineffective? An Experimental and Longitudinal Study. Journal of Learning Disabilities, Vol 30, No. 3, pages 414-431.

- Snowling, M. J. (2012), Early identification and interventions for dyslexia: a contemporary view. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs. Vol 13, Issue 1, pages 7-14.

- Van Leeuwen, T., Been, P., et al. (2006). Mismatch response is absent in 2-month-old infants at risk for dyslexia. Neuroreport. Vol. 17, Issue 4, pp 351-355. van Leeuwen, T., Been, P., et al. (2008).

- Two-month-old infants at risk for dyslexia do not discriminate /bAk/ from /dAk/: A brain-mapping study. Journal of Neurolinguistics. Vol 21, Issue 4, pp 333-348.

- Wybrow, D. & Hanley, J.R. (2012, August). Subtypes of developmental dyslexia: Stanovich et al. (1997) revisited. Talk presented at BPS cognitive section conference, Glasgow.

- Shaywitz S.E., Shaywitz B.A., Fulbright R, et al (2003). Neural Systems for Compensation and Persistence: Young Adult Outcome of Childhood Reading Disability. Biological Psychiatry 54:25-33.

- Horwitz B, Rumsey J.M., Donahue B.C. (1998), Functional connectivity of the angular gyrus and dyslexia. Neurobiology: 95: 8939-8944.

- Hoeft F., McCandliss B.D., Black J.M/, et al (2011). Neural systems predicting long-term outcome in dyslexia. PNAS, Vol. 108, No. 1, pp 361-366.