Education vs. Child Development: How Dyslexia Happens

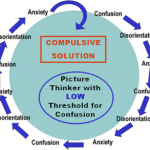

Having been functionally illiterate for the first 38 years of my life, and having overcome the problem sufficiently to write a book and read it onto tape, here is what I’ve found out: dyslexia is not the result of brain damage or nerve damage. Nor is it caused by a malformation of the brain, inner ear or eyeballs. It is the product of a special mode of thought and a natural reaction to confusion.

Having been functionally illiterate for the first 38 years of my life, and having overcome the problem sufficiently to write a book and read it onto tape, here is what I’ve found out: dyslexia is not the result of brain damage or nerve damage. Nor is it caused by a malformation of the brain, inner ear or eyeballs. It is the product of a special mode of thought and a natural reaction to confusion.

Before the invention of written language, dyslexia didn’t exist. People with the gift of dyslexia were probably the custodians of oral history because of their excellent ability to memorize and transmit the spoken word.

This is really a disability of our language and the educational process. From my experience in working with more than 1,000 dyslexics, this is how the syndrome develops during childhood.

- A child who is potentially dyslexic discovers how to mentally fill in fragmentary perceptions at an age as early as three months. This imaginative talent may later produce dyslexia.

- During early childhood, the child uses this talent to recognize objects in the environment and to develop artistic and kinesthetic talents. The child becomes a visual and conceptual thinker. There is little need for development of verbal thought, a slower mode of thinking characterized by an internal monologue of words.

- The child is expected to begin reading in kindergarten or early grade school. Written language—composed of phonetic symbols—is a puzzle. By this time, the child automatically disorients the perceptions to recognize and understand things in the environment. It works fine with the real world, but viewing printed letters upside down or reversed or in the wrong order makes them less recognizable.

- The child becomes increasingly confused, which produces more disorientation. The child suspects something is wrong. This is confirmed by the teacher, the other kids in the class, the school administration, and eventually the parents. Everybody gets upset, so the “cognitively challenged” child also gets upset. Now we may see behavior problems.

- Unless someone intervenes and provides appropriate learning methods, the child has no choice but to struggle through as much school as tolerable, possibly in a Special Education class or under the influence of drugs like Ritalin or Cylert.

- At the age of eight or nine, the child invents tricks like rote memorization, avoidance and reliance on others for reading and writing skills. In practical classes like science, music, art or shop, this child may excel, but classes that require much reading and writing are torture.

- Unless there is proper intervention by someone who shows compassion and respect, the dyslexic child’s self-esteem will suffer.

- After escaping from school, the person begins to overcome or circumvent the “handicap” of being functionally illiterate. Dyslexics often excel on the job, even though they are functionally illiterate.

- By the time the dyslexic becomes an adult, the inability to read and write well is a shameful secret. The person is convinced that it is a sign not only of ignorance, but unworthiness. This unfortunate self-perception can make adult dyslexics secretive and hostile.

How can we prevent children from losing their self-esteem? As my colleague Dr. Ali has said, erase words like “dumb,” “stupid” and “challenged” from your vocabulary. Never criticize them for mistakes or imply something is wrong with them. Gain an understanding of how dyslexics think and emphasize their strong points. Find appropriate methods to help them learn to read, write and study. Remember that some bright kids aren’t ready to start reading until they’re eight or nine. They will catch up faster without the burden of self-doubt.

In tutoring kids, treat symbols and words as games or puzzles to be solved. Make language fun.

Language skills are dandy, but there is much to be said for real life skills and experiential learning. Give dyslexics credit for these abilities, and you may discover that their “learning disability” is really genius in disguise—or at least a high level of intelligence and ability, which they had since the day they were born.