Brain Scans Show Dyslexics Read Better with Alternative Strategies

Scientists studying the brain have found that dyslexic adults who become capable readers use different neural pathways than nondyslexics. This research shows that there are at least two independent systems for reading: one that is typical for the majority of readers, and another that is more effective for the dyslexic thinker

NIMH Study of Dyslexic Adults

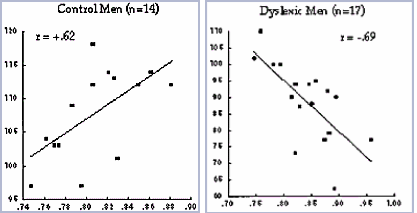

Researchers Judith Rumsey and Barry Horwitz at the National Institute of Mental Health used positron emission tomography (PET) to compare regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) among dyslexic and nondyslexic men. The dyslexic subjects had childhood histories of dyslexia and continued to show some symptoms related to reading, but their overall reading ability varied. For some word recognition and comprehension tasks, the dyslexic men scored as well as or better than controls.

Research correlating brain activity with reading ability showed an intriguing inverse relationship between reading ability and cerebral blood flow patterns. For nondyslexic controls, stronger activation of left hemispheric reading systems, including the left angular gyrus, corresponded to better reading skill. For dyslexic subjects, the opposite was true: the stronger the left-hemispheric pattern, the poorer the reader. In contrast, increased reading skill for dyslexics was correlated with greater reliance on the right hemispheric systems.

The researchers explained:

“The rCBF–reading test correlations identified a region in/near the left angular gyrus as significantly related to level of reading skill within both groups. These correlations were uniformly positive for the control group and uniformly negative for the dyslexic group, indicating diametrically opposed relationships in the two groups….within the control group higher rCBF was associated with better reading skill and that within the dyslexic group higher rCBF was associated with worse reading skill, or more severe dyslexia.”

The researchers observed a similar pattern in the right hemisphere, in an area near the right angular gyrus. In the right brain area, the dyslexic men had higher activation levels than controls during the word reading tasks, which correlated positively to improved reading ability. For the nondyslexic control group, such activation pattern was negatively correlated to reading ability.

Comparison of Reading Outcomes among children followed since kindergarten

A team of researchers led by Sally Shaywitz at Yale University confirmed that dyslexic individuals who become good readers have a different pattern of brain use than either nondyslexic readers, or dyslexics who still read poorly. The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to evaluate brain activity among 20-year-old dyslexic men and women selected from a group that had been followed since kindergarten. All the dyslexic subjects had a history of severe reading impairment in early childhood. However, while some of the students continued to struggle with reading throughout their school years (“persistently poor readers”), others improved by their high school years, becoming accurate readers with strong comprehension skills (“accuracy improved readers”).

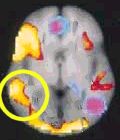

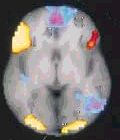

Dyslexic subjects from both groups as well as non-dyslexic control subjects were asked to perform reading tasks involving phonological processing (non-word rhyming test) and ascertaining meaning (semantic category test).

Differences with Phonetic Processing

During the non-word rhyming test (“Do leat and jete rhyme?), both dyslexic groups showed less activation of the left posterior and temporal areas of the brain as compared to the control group. However, the dyslexics who were improved readers also had greater activation of right temporal areas and both right and left frontal areas.

Differences on Meaning-Based Tasks

For the semantic category test (“Are corn and rice in the same category?”) the persistently poor readers showed brain activity very similar to the nondyslexic control group, despite the fact that their reading performance was significantly impaired. Like the control group, the persistently poor readers activate left posterior and temporal systems. In contrast, the improved dyslexic readers bypassed this area entirely.

Impact of Findings for Education

These brain imaging studies show that teaching methods that may work well for a large majority of schoolchildren may be counterproductive when used with dyslexic children. Teaching methods based on intensive or systematic drill in phonemic awareness or phonetic decoding strategies may actually be harmful to dyslexic children. Such teaching might simply emphasize reliance on mental strategies that are as likely to diminish reading ability for dyslexic children as they are to improve it, increasing both the frustration and impairment level of dyslexic students.

Davis Theory and Methods

Davis Learning Strategies® and Davis Dyslexia Correction® emphasize a creative, meaning-based strategy for acquisition of basic reading skills. Children (and adults) use clay to model the concepts that are associated with word meanings at the same time as modeling the letters of each word in clay. At the primary level, these methods provide a route to learning to read that seems easier for students with dyslexic tendencies than traditional instruction. Among older dyslexic children and adults, these methods routinely lead to very rapid progress in reading ability.

Modeling words in clay may help build the mental pathways that brain scan evidence shows to be crucial for reading development among dyslexic students.

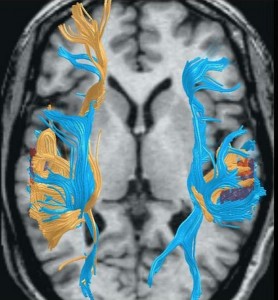

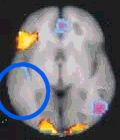

This image combines a DTI (diffusion tensor image) image showing white matter pathways in the brain of a dyslexic man (in blue) overlaid on an image of the brain pathways of a person with more typical brain architecture (in gold).

The image shows that while the dyslexic man has somewhat less well-developed left brain connections, his right brain connections ae far more extensive than his non-dyslexic counterpart.

(From Leonard & Ekhert, Assymetry and Dyslexia)