The Visual Spatial Learner

What is a Visual-Spatial Learner?

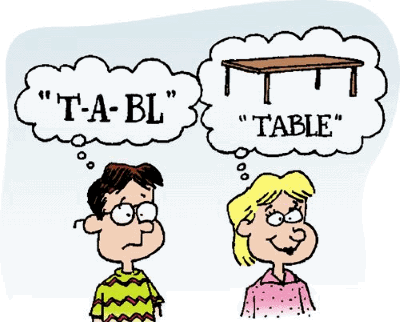

A visual-spatial learner is a student who learns holistically rather than in a step-by-step fashion. Visual imagery plays an important role in the student’s learning process. Because the individual is processing primarily in pictures rather than words, ideas are interconnected (imagine a web). Linear sequential thinking — the norm in American education — is particularly difficult for this person and requires a translation of his or her usual thought processes, which often takes more time.

A visual-spatial learner is a student who learns holistically rather than in a step-by-step fashion. Visual imagery plays an important role in the student’s learning process. Because the individual is processing primarily in pictures rather than words, ideas are interconnected (imagine a web). Linear sequential thinking — the norm in American education — is particularly difficult for this person and requires a translation of his or her usual thought processes, which often takes more time.

Some visual-spatial learners are excellent at auditory sequential processing as well. They have full access to both systems, so that if they don’t get an immediate “aha” when they are looking at a problem, they can resort to sequential, trial-and-error methods of problem solving. These students are usually highly gifted with well integrated abilities. However, the majority of visual-spatial learners we have found in our work are deficient in auditory sequential skills. This leads to a complex set of problems for the student. A definite mismatch exists between the student’s learning style and the instructional methods employed by the student’s teachers.

Physiological and Personality Factors.

Visual-spatial learners who experience learning problems have heightened sensory awareness to stimuli, such as extreme sensitivity to smells, acute hearing and intense reactions to loud noises. They are constantly bombarded by stimuli; they get so much information that they have trouble filtering it out. They tend to have excellent hearing, but poor listening skills. Their ability to retain and comprehend information auditorily is weak and they have difficulty with sequential tasks.

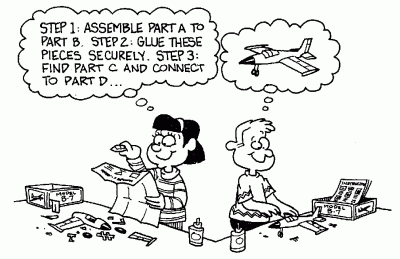

These children are highly perfectionistic, which means that they cannot handle failure. They usually refuse to attempt trial-and-error learning because they can’t cope with the failure inherent in this technique. They have an all-or-none learning style (the aha phenomenon). They either immediately see the correct solution to a problem or they don’t get it at all, in which case they may watch quietly (while pretending not to watch) or avoid the situation completely because it is too ego threatening.

These children are highly perfectionistic, which means that they cannot handle failure. They usually refuse to attempt trial-and-error learning because they can’t cope with the failure inherent in this technique. They have an all-or-none learning style (the aha phenomenon). They either immediately see the correct solution to a problem or they don’t get it at all, in which case they may watch quietly (while pretending not to watch) or avoid the situation completely because it is too ego threatening.

Visual-spatial learners have amazing abilities to “read” people. Since they can’t rely on audition for information, they develop remarkable visual and intuitive abilities, including reading body language and facial expressions.

Many of the students described in this article were so adept at reading cues and observing people that they could tell what a person was thinking almost verbatim. Oftentimes, in school, they sense a teacher’s anxieties and ambivalent feeling towards them, and react with statements such as, “that teacher hates me.”

Traditional Education

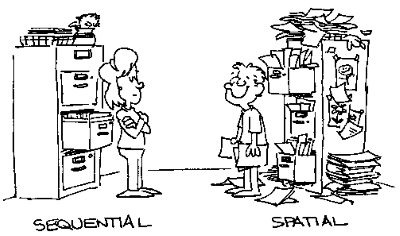

In most cases, the visual-spatial learning style is not addressed in school, and these students’ self-esteem suffers accordingly. Traditional teaching techniques are designed for the learning style of sequential learners. Concepts are introduced in a step-by-step fashion, practiced with drill and repetition, assessed under timed conditions, and then reviewed. This process is ideal for sequential learners whose learning progresses in a step-by-step manner from easy to difficult material.

By way of contrast, spatial learners are systems thinkers-they need to see the whole picture before they can understand the parts. They are likely to see the forest and miss the trees. They are excellent at mathematical analysis but may make endless computational errors because it is difficult for them to attend to details. Their reading comprehension is usually much better than their ability to decode words.

Concepts are quickly comprehended when they are presented within a context and related to other concepts. Once spatial learners create a mental picture of a concept and see how the information fits with what they already know, their learning is permanent. Repetition is completely unnecessary and irrelevant to their learning style.

Concepts are quickly comprehended when they are presented within a context and related to other concepts. Once spatial learners create a mental picture of a concept and see how the information fits with what they already know, their learning is permanent. Repetition is completely unnecessary and irrelevant to their learning style.

However, without easily observable connecting ties, the information cannot take hold anywhere in the brain — it is like learning in a vacuum, and seems to the student like pointless exercises in futility. Teachers often misinterpret the student’s difficulties with the instructional strategies as inability to learn the concepts and assume that the student needs more drill to grasp the material. Rote memorization and drill are actually damaging for visual-spatial learners, since they emphasize the students’ weaknesses instead of their strengths. When this happens, the student gets caught up in a spiraling web of failure, assumes he is stupid, loses all motivation, and hates school. Teachers then assume that the student doesn’t care or is being lazy, and behavior problems come to the fore. Meanwhile, the whole cycle creates a very deep chasm in the student’s self-esteem.

In the traditional school situation the atmosphere is often hostile to visual-spatial learners and their skills. The students are visual, whereas instruction tends to be auditory: phonics, oral directions, etc. The students are gestalt, aha learners and can be taught out of order, whereas the curriculum is sequential, with orderly progressions of concepts and ideas. The students are usually disorganized and miss details, whereas most teachers stress organization and attention to detail. The student is highly aware of space but pays little attention to time, whereas school functions on rigid time schedules.

Conclusion

A key component in the recovery of motivation for visual-spatial learners is experiencing success. Individual tutoring should be sought to help these students learn to use their strengths and build their feelings of competence. Sincere praise works wonders. Spatial learners often excel at activities such as Legos, computer games, art or music. Any skill in which these young people experience success should be encouraged and nurtured. Their skills, interests and hobbies may lead to careers in adult life.

In adulthood, these individuals excel in fields dependent upon their spatial abilities: art, architecture, physics, aeronautics, pure mathematical research, engineering, computer programming, and photography. Frequently, they develop their own businesses or become chief executive officers (CEOs) in major corporations because of their inventiveness and ability to see the relationships of large numbers of variables. We need individuals with highly developed visual-spatial abilities for advancement in the arts, technology and business. These are the creative leaders of society. We need to protect their differences in childhood and enable them to develop their unique talents in supportive environments at home and at school.